Inline conditionals in CSS, now?

The CSS WG resolved to add if() to CSS, but that won’t be in browsers for a while.

What are our options in the meantime?

A couple days ago, I posted about the recent CSS WG resolution to add an if() function to CSS.

Great as it may be, this is still a long way off, two years if everything goes super smoothly, more if not.

So what can you do when you need conditionals right now?

You may be pleased to find that you’re not completely out of luck. There is a series of brilliant, horrible hacks that enable you to expose the kinds of higher level custom properties that conditionals typically enable.

Using hacks in production?!

The instinctive reaction many developers have when seeing hacks like these is “Nice hack, but can’t possibly ever use this in production”. This sounds reasonable on the surface (keeping the codebase maintainable is a worthy goal!) but when examined deeply, it reflects the wrong order of priorities, prioritizing developer convenience over user convenience.

The TAG maintains a Web Platform Design Principles document [1] that everyone designing APIs for the web platform is supposed to read and follow. I’m a strong believer in having published Design Principles, for any product[2]. They help stay on track, and remember what the big picture vision is, which is otherwise easy to lose sight of in the day to day minutiae. One of the core principles in the document is the Priority of Constituencies. The core of it is:

User needs come before the needs of web page authors, which come before the needs of user agent implementors, which come before the needs of specification writers, which come before theoretical purity.

Obviously in most projects there are far fewer stakeholders than for the whole web platform, but the spirit of the principle still applies: the higher the abstraction, the higher priority the user needs. Or, in other words, consumers above producers.

For a more relatable example, in a web app using a framework like e.g. Vue and several Vue components, the user needs of website users come before the needs of the web app developers, which come before the needs of the developers of its Vue components, which come before the needs of the Vue framework developers (sorry Evan :).

The TAG did not invent this principle; it is well known in UX and Product circles with a number of different wordings:

- “Put the pain on those who can bear it”

- Prefer internal complexity over external complexity

Why is that? Several reasons:

- It is far easier to change the implementation than to change the user-facing API, so it’s worth making sacrifices to keep it clean from the get go.

- Most products have way more users than developers, so this minimizes collective pain.

- Internal complexity can be managed far more easily, with tooling or even good comments.

- Managing complexity internally localizes it and contains it better.

- Once the underlying platform improves, only one codebase needs to be changed to reap the benefits.

The corollary is that if hacks allow you to expose a nicer API to component users, it may be worth the increase in internal complexity (to a degree). Just make sure that part of the code is well commented, and keep track of it so you can return to it once the platform has evolved to not require a hack anymore.

Like all principles, this isn’t absolute. A small gain in user convenience is not a good tradeoff when it requires tremendous implementation complexity. But it’s a good north star to follow.

As to whether custom properties are a better option to control styling than e.g. attributes, I listed several arguments for that in my previous article. Although, there are also cases where using custom properties is not a good idea…

When is it not a good idea to do this?

In a nutshell, when the abstraction is likely to leak. Ugliness is only acceptable if it’s encapsulated and not exposed to component users. If there is a high chance they may come into contact with it, it might be a better idea to simply use attributes and call it a day.

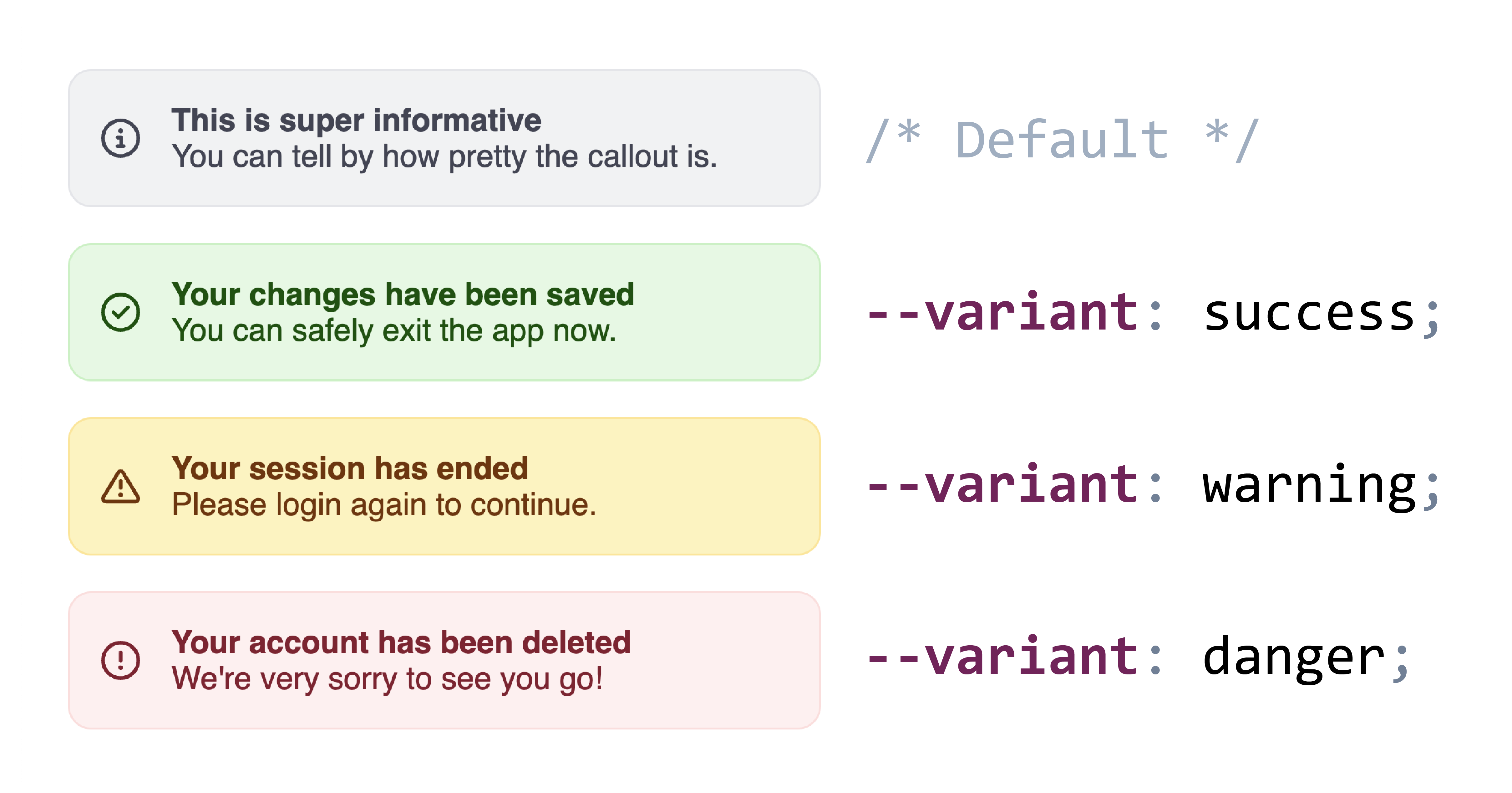

In many of the examples below, I use variants as the canonical example of a custom property that a component may want to expose.

However, if component consumers may need to customize each variant, it may be better to use attributes so they can just use e.g. [variant="success"] instead of having to understand whatever crazy hack was used to expose a --variant custom property.

And even from a philosophical purity perspective, variants are on the brink of presentational vs semantic anyway.

The current state of the art

There is a host of hacks and workarounds that people have come up with to make up for the lack of inline conditionals in CSS, with the first ones dating back to as early as 2015.

1. Binary Linear Interpolation

This was first documented by Roma Komarov in 2016, and has since been used in a number of creative ways.

The gist of this method is to use essentially the linear interpolation formula for mapping

However, instead of using this to map a range to another range,

we use it to map two points to two other points,

basically the two extremes of both ranges:

This was Roma’s original example:

:root {

--is-big: 0;

}

.is-big {

–is-big: 1;

}

.block {

padding: calc(

25px * var(–is-big) +

10px * (1 - var(–is-big))

);

border-width: calc(

3px * var(–is-big) +

1px * (1 - var(–is-big))

);

}

He even expands it to multiple conditions by multiplying the interpolation factors.

E.g. this code snippet to map 0 to 100px, 1 to 20px, and 2 to 3px:

.block {

padding: calc(

100px * (1 - var(--foo)) * (2 - var(--foo)) * 0.5 +

20px * var(--foo) * (2 - var(--foo)) +

3px * var(--foo) * (1 - var(--foo)) * -0.5

);

}

Which these days could be rewritten as this, which also makes the boolean logic at play clearer:

.block {

--if-not-0: min(max(0 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 0), 1);

--if-not-1: min(max(1 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 1), 1);

--if-not-2: min(max(2 - var(--foo), var(--foo) - 2), 1);

–if-0: var(–if-not-1) * var(–if-not-2);

–if-1: var(–if-not-0) * var(–if-not-2);

–if-2: var(–if-not-0) * var(–if-not-1);

padding: calc(

100px * var(–if-0) +

20px * var(–if-1) +

3px * var(–if-2)

);

}

Back then, min() and max() were not available, so he had to divide each factor by an obscure constant to make it equal to 1 when it was not 0.

Once abs() ships this will be even simpler (the inner max() is basically getting the absolute value of N - var(--foo))

Ana Tudor also wrote about this in 2018, in this very visual article: DRY Switching with CSS Variables. Pretty sure she was also using boolean algebra on these too (multiplication = AND, addition = OR), but I couldn’t find the exact post.

2. Toggles (Space Toggle, Cyclic Toggles)

This was independently discovered by Ana Tudor (c. 2017), Jane Ori in April 2020 (who gave it the name “Space Toggle”), David Khoursid (aka David K Piano) in June 2020 (he called it prop-and-lock), and yours truly in Oct 2020 (I called it the --var: ; hack, arguably the worst name of the three 😅).

The core idea is that var(--foo, fallback) is actually a very limited form of conditional: if --foo is initial (or IACVT), it falls back to fallback, otherwise it’s var(--foo).

Furthermore, we can set custom properties (or their fallbacks) to empty values to get them to be ignored when used as part of a property value.

It looks like this:

:root {

--if-success: ;

--if-warning: ;

}

.success {

--if-success: initial;

}

.warning {

–if-warning: initial;

}

.callout {

background:

var(–if-success, var(–color-success-90))

var(–if-warning, var(–color-warning-90));

}

One of the downsides of this version is that it only supports two states per variable.

Note how we needed two variables for the two states.

Another downside is that there is no way to specify a fallback if none of the relevant variables are set.

In the example above, if neither --if-success nor --if-warning are set, the background declaration will be empty, and thus become IACVT which will make it transparent.

Cyclic Toggles

In 2023, Roma Komarov expanded the technique into what he called “Cyclic Dependency Space Toggles” which

addresses both limitations:

it supports any number of states,

and allows for a default value.

The core idea is that variables do not only become initial when they are not set, or are explicitly set to initial,

but also when cycles are encountered.

Roma’s technique depends on this behavior by producing cycles on all but one of the variables used for the values. It looks like this:

.info {

--variant: var(--variant-default);

–variant-default: var(–variant,);

–variant-success: var(–variant,);

–variant-warning: var(–variant,);

–variant-error: var(–variant,);

background:

var(–variant-default, lavender)

var(–variant-success, palegreen)

var(–variant-warning, khaki)

var(–variant-error, lightpink);

}

And is used like this:

.my-warning {

--variant: var(--variant-warning);

}

A downside of this method is that since the values behind the --variant-success, --variant-warning, etc variables are specific to the --variant variable

they need to be namespaced to avoid clashes.

Layered Toggles

A big downside of most of these methods (except for the animation-based ones) is that you need to specify all values of the property in one place, and the declaration gets applied whether your custom property has a value or not, which makes it difficult to layer composable styles leading to some undesirable couplings.

Roma Komarov’s “Layered Toggles” method addresses this for some cases

by allowing us to decouple the different values by taking advantage of Cascade Layers.

The core idea is that Cascade Layers include a revert-layer keyword that will cause the current layer to be ignored wrt the declaration it’s used on.

Given that we can use unnamed layers, we can simply user a @layer {} rule for every block of properties we want to apply conditionally.

This approach does have some severe limitations which made it rather unpractical for my use cases. The biggest one is that anything in a layer has lower priority than any unlayered styles, which makes it prohibitive for many use cases. Also, this doesn’t really simplify cyclic toggles, you still need to set all values in one place. Still, worth a look as there are some use cases it can be helpful for.

3. Paused animations

The core idea behind this method is that paused animations (animation-play-state: paused) can still be advanced by setting animation-delay to a negative value.

For example in an animation like animation: 100s foo, you can access the 50% mark by setting animation-delay: -50s.

It’s trivial to transform raw numbers to <time> values, so this can be abstracted to plain numbers for the user-facing API.

Here is a simple example to illustrate how this works:

@keyframes color-mixin {

0% { background: var(--color-neutral-90); border-color: var(--color-neutral-80); }

25% { background: var(--color-success-90); border-color: var(--color-success-80); }

50% { background: var(--color-warning-90); border-color: var(--color-warning-80); }

75% { background: var(--color-danger-90); border-color: var(--color-danger-80); }

}

button {

animation: foo 100s calc(var(–variant) * -100s / 4 ) infinite paused;

}

Used like:

.error button {

--variant: 2;

}

This is merely to illustrate the core idea, having a --variant property that takes numbers is not a good API!

Though the numbers could be aliased to variables, so that users would set --variant: var(--success).

This technique seems to have been first documented by me in 2015, during a talk about …pie charts (I would swear I showed it in an earlier talk but I cannot find it). I never bothered writing about it, but someone else did, 4 years later.

To ensure you don’t get slightly interpolated values due to precision issues, you could also slap a steps() in there:

button {

animation: foo 100s calc(var(--variant) * -100s / 4 ) infinite paused steps(4);

}

This is especially useful when 100 divided by your number of values produces repeating decimals,

e.g. 3 steps means your keyframes are at increments of 33.33333%.

A benefit of this method is that defining each state is done with regular declarations, not involving any weirdness, and that .

It does also have some obvious downsides:

- Values restricted to numbers

- Takes over the

animationproperty, so you can’t use it for actual animations.

4. Type Grinding

So far all of these methods impose constraints on the API exposed by these custom properties: numbers by the linear interpolation method and weird values that have to be hidden behind variables for the space toggle and cyclic toggle methods.

In October 2022, Jane Ori was the first one to discover a method that actually allows us to support plain keywords, which is what the majority of these use cases needs. She called it “CSS-Only Type Grinding”.

Its core idea is if a custom property is registered (via either @property or CSS.registerProperty()),

assigning values to it that are not valid for its syntax makes it IACVT (Invalid at computed value time) and it falls back to its initial (or inherited) value.

She takes advantage of that to progressively transform keywords to other keywords or numbers through a series of intermediate registered custom properties, each substituting one more value for another.

I was recently independently experimenting with a similar idea.

It started from a use case of one of my components where I wanted to implement a --size property with two values: normal and large.

Style queries could almost get me there, but I also needed to set flex-flow: column on the element itself when --size was large.

The end result takes N + 1 @property rules, where N is the number of distinct values you need to support.

The first one is the rule defining the syntax of your actual property:

@property --size {

syntax: "normal | large",

initial-value: normal;

inherits: true;

}

Then, you define N more rules, each progressively substituting one value for another:

@property --size-step-1 {

syntax: "row | large";

initial-value: row;

inherits: false;

}

@property --size-step-end {

syntax: "row | column";

initial-value: column;

inherits: false;

}

And at the component host you daisy chain them like this:

:host {

--size-step-1: var(--size);

--size-step-end: var(--size-step-1);

flex-flow: var(--size-step-end);

}

And component consumers get a really nice API:

.my-component {

--size: large;

}

You can see it in action in this codepen:

See the Pen Transform keywords to other keywords (2 keyword version) by Lea Verou (@leaverou) on CodePen.

You can use the same general idea to transform more keywords or to transform keywords into different sets of keywords for use in different properties.

We can also transform keywords to numbers, by replacing successive keywords with <integer> in the syntax, one at a time, with different initial values each time.

Here is the --variant example using this method:

@property --variant {

syntax: "none | success | warning | danger";

initial-value: none;

inherits: true;

}

@property --variant-step-1 {

syntax: "none | <integer> | warning | danger";

initial-value: 1;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-step-2 {

syntax: "none | <integer> | danger";

initial-value: 2;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-step-3 {

syntax: "none | <integer>";

initial-value: 3;

inherits: false;

}

@property --variant-index {

syntax: "<integer>";

initial-value: 0;

inherits: false;

}

.callout {

–variant-step-1: var(–variant);

–variant-step-2: var(–variant-step-1);

–variant-step-3: var(–variant-step-2);

–variant-index: var(–variant-step-3);

/* Now use --variant-index to set other values */

}

Then, we can use techniques like linear range mapping to transform it to a length or a percentage (generator)

or recursive color-mix() to use that number to select an appropriate color.

5. Variable animation name

In 2018, Roma Komarov discovered another method that allows plain keywords to be used as the custom property API,

forgot about it, then rediscovered it in June 2023 😅.

He still never wrote about it, so these codepens are the only documentation we have.

It’s a variation of the previous method: instead of using a single @keyframes rule and switching between them via animation-delay,

define several separate @keyframes rules, each named after the keyword we want to use:

@keyframes success {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-success-90);

border-color: var(--color-success-80);

}

}

@keyframes warning {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-warning-90);

border-color: var(--color-warning-80);

}

}

@keyframes danger {

from, to {

background-color: var(--color-danger-90);

border-color: var(--color-danger-80);

}

}

.callout {

padding: 1em;

margin: 1rem;

border: 3px solid var(–color-neutral-80);

background: var(–color-neutral-90);

animation: var(–variant) 0s paused both;

}

Used like:

.warning {

--variant: warning;

}

The obvious downsides of this method are:

- Impractical to use outside of Shadow DOM due to the potential for name clashes.

- Takes over the

animationproperty, so you can’t use it for actual animations.

Improvements

Every one of these methods has limitations, some of which are inerent in its nature, but others can be improved upon. In this section I will discuss some improvements that me or others have thought of. I decided to include these in a separate section, since they affect more than one method.

Making animation-based approaches cascade better

A big downside with the animation-based approaches (3 and 5) is the place of animations in the cascade:

properties applied via animation keyframes can only be overridden via other animations or !important.

One way to deal with that is to set custom properties in the animation keyframes, that you apply in regular rules. To use the example from Variable animation name:

@keyframes success {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-success-90);

--border-color: var(--color-success-80);

}

}

@keyframes warning {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-warning-90);

--border-color: var(--color-warning-80);

}

}

@keyframes danger {

from, to {

--background-color: var(--color-danger-90);

--border-color: var(--color-danger-80);

}

}

.callout {

padding: 1em;

margin: 1rem;

border: 3px solid var(–border-color, var(–color-neutral-80));

background-color: var(–background-color, var(–color-neutral-90));

animation: var(–variant) 0s paused both;

}

Note that you can combine the two approaches (variable animation-name and paused animations)

when you have two custom properties where each state of the first corresponds to N distinct states of the latter.

For example, a --variant that sets colors, and a light/dark mode within each variant that sets different colors.

Making animation-based approaches compose better with author code

Another downside of the animation-based approaches is that they take over the animation property.

If authors want to apply an animation to your component, suddenly a bunch of unrelated things stop working, which is not great user experience.

There isn’t that much to do here to prevent this experience, but you can at least offer a way out:

instead of defining your animations directly on animation, define them on a custom property, e.g. --core-animations.

Then, if authors want to apply their own animations, they just make sure to also include var(--core-animations) before or after.

Discrete color scales

Many of the approaches above are based on numerical values, which are then mapped to the value we actually want. For numbers or dimensions, this is easy. But what about colors?

I linked to Noah Liebman’s post above on recursive color-mix(),

where he presents a rather complex method to select among a continuous color scale based on a 0-1 number.

However, if you don’t care about any intermediate colors and just want to select among a few discrete colors, the method can be a lot simpler. Simple enough to be specified inline.

Let me explain: Since color-mix() only takes two colors, we need to nest them to select among more than 2, no way around that.

However, the percentages we calculate can be very simple: 100% when we want to select the first color and 0% otherwise.

I plugged these numbers into my CSS range mapping tool

(example) and noticed a pattern:

If we want to output 100% when our variable (e.g. --variant-index) is N-1 and 0% when it’s N, we can use 100% * (N - var(--variant-index)).

We can use this on every step of the mixing:

background: color-mix(in oklab,

var(--stone-2) calc(100% * (1 - var(--color-index, 0))), /* default color */

color-mix(in oklab,

var(--green-2) calc(100% * (2 - var(--color-index))),

color-mix(in oklab,

var(--yellow-2) calc(100% * (3 - var(--color-index))),

var(--red-2)

)

)

);

But what happens when the resulting percentage is < 0% or > 100%?

Generally, percentages outside [0%, 100%] make color-mix() invalid,

which would indicate that we need to take care to keep our percentages within that range (via clamp() or max()).

However, within math functions there is no parse-time range-checking,

so values are simply clamped to the allowed range.

Here is a simple example that you can play with (codepen):

See the Pen Discrete color scales with simpler recursive color-mix() by Lea Verou (@leaverou) on CodePen.

And here is a more realistic one, using the Type Grinding method to transform keywords to numbers, and then using the above technique to select among 4 colors for backgrounds and borders (codepen).

Combining approaches

There are two components to each method: the input values it supports, i.e. your custom property API that you will expose, e.g. numbers, keywords, etc.,

and the output values it supports (<dimension>, keywords, etc.).

Even without doing anything, we can combine methods that support the same type of input values, e.g. Binary Linear Interpolation and Paused animations or Type Grinding and Variable animation names.

If we can transform the input values of one method to the input values of another, we can mix and match approaches to maximize flexibility. For example, we can use type grinding to transform keywords to numbers, and then use paused animations or binary linear interpolation to select among a number of quantitative values based on that number.

- Keywords → Numbers

- Type grinding

- Numbers → Keywords

- We can use paused animations to select among a number of keywords based on a number (which we transform to a negative

animation-delay). - Space toggles → Numbers

- Easy:

--number: calc(0 var(--toggle, + 1)) - Numbers → Space toggles

- Once again, Roma Komarov has come up with a very cool trick: he conditionally applies an animation which interpolates two custom properties from

initialto the empty value and vice versa — basically variable animation names but used on an internal value. Unfortunately a Firefox bug prevents it from working interoperably. He also tried a variant for space toggles but that has even worse compatibility, limited to Chrome only. I modified his idea a bit to use paused animations instead, and it looks like my attempt works on Firefox as well. 🎉

So, which one is better?

I’ve summarized the pros and cons of each method below:

| Method | Input values | Output values | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Quantitative |

|

|

|

|

|

Any |

|

|

|

| Numbers | Any |

|

|

|

| Keywords |

Any value supported by the |

|

|

|

| Keywords | Any |

|

|

The most important consideration is the API we want to expose to component users. After all, exposing a nicer API is the whole point of this, right?

If your custom property makes sense as a number without degrading usability

(e.g. --size may make sense as a number, but small | medium | large is still better than 0 | 1 | 2),

then Binary Linear Interpolation is probably the most flexible method to start with,

and as we have seen in Combining approaches section, numbers can be converted to inputs for every other method.

However, in the vast majority of cases I have seen, the north star API is a set of plain, high-level keywords. This is only possible via Type Grinding and Variable animation names.

Between the two, Type Grinding is the one providing the best encapsulation, since it relies entirely on custom properties and does not hijack any native properties.

Unfortunately, the fact that @property is not yet supported in Shadow DOM throws a spanner in the works,

but since these intermediate properties are only used for internal calculations,

we can just give them obscure names and insert them in the light DOM.

On the other hand, @keyframes are not only allowed, but also properly scoped when used in Shadow DOM,

so Variable animation name might be a good choice when you don’t want to use the same keywords for multiple custom properties on the same component

and its downsides are not dealbreakers for your particular use case.

Conclusion

Phew! That was a long one. If you’re aware of any other techniques, let me know so I can add them.

And I think after all of this, if you had any doubt that we need if() in CSS,

the sheer number and horribleness of these hacks must have dispelled it by now. 😅

Thanks to Roma Komarov for reviewing earlier drafts of this article.